Background

Content warning: audio testimony depicting graphic police violence.

Below you will find a timeline that delves into some of how DRUM members, organizers, and volunteers organized in the context of immigrants becoming the fastest growing percentage of the prison population at the beginning of the century--a statistic that was only exacerbated by the repressive immigration policies of the post 9/11 period. Some political context for the timeline is offered in this section.

You're encouraged to explore the timeline and reflect on the media offered. You will encounter testimonies from detainees inside jails and detention centers, flyers encouraging community members to turn out to actions and KYR workshops, and photos that make this history feel even closer to our present moment.

This timeline will be updated on a weekly basis up to the present day.

As we mark 20 years of the attacks on U.S. soil on September 11th and the escalation of state sanctioned racial profilings and detentions in the years that followed, it becomes more and more necessary to situate the attacks on working class South Asian, Muslim, Arab, and Indo-Caribbean communities as a part of a much longer history of how the U.S. has and continues to wage wars both internationally and domestically. As many who organized and fought back in this period observed, police collaboration with INS and indefinite detentions were not anomalous tactics that the government suddenly developed and deployed. At the time, the disappearing of hundreds of boys and men from our communities recalled Japanese internment camps set up during the Second World War. Organizers and activists drew parallels between the prison industrial complex’s impact on Black and Latinx communities and immigrant detentions, highlighting the profit motive for jails to take on more detainees. The so-called “war on terror” became another name on a list of U.S. domestic wars alongside the “war on drugs” that targeted poor Black and Brown folks and the numerous genocidal wars first waged against the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island to steal their ancestral lands. And, as is the history with U.S. war, the domestic is inseparable from the international—tactics used on detainees at county jails were later seen with prisoners in the occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Many working class immigrant communities lived the realities of the tightening grip the U.S. had on the world. Economic, political and imperial. wars in homelands triggered crises which forced people to leave for the U.S. where they were subjected to continued systemic violence. And if not war and overt violence, then it was the force of U.S. global capitalism that drove people to have no option but to leave for the belly of the empire. Towards the end of the first period of this timeline, it becomes clear that these post 9/11 immigration policies were not just limited to South Asian, Arab, and Muslim communities but had lasting impacts on immigrants from all over Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, and Asia. Despite surviving conditions of perpetual war within the U.S. and their homelands, working class immigrants embody both the destructive impact of state violence and tremendous possibilities for organizing solidarity that transforms and builds the world that we want to see.

In 2001, DRUM was one year old. Working class South Asian communities—street vendors, domestic workers, youth, recent immigrants—had identified the racial targeting of their community by the NYPD and INS as a critical issue to address. As a result, DRUM began the INS De-Detention Program to educate community members on their rights and launched a project to visit INS detainees at New Jersey detention centers in order to connect them to resources. Meanwhile, South Asian youth organized workshops at community gatherings, schools, and other organizations to bring attention to the issues in the community like the unequal treatment of women, harassment and abuse from the NYPD, and wage discrimination based on documentation status.

While the attacks on September 11, 2001 drastically increased xenophobia in the U.S., DRUM continued to focus on racial and class violence as a key issue for working class South Asians in New York City. Days after the attacks, DRUM organized a hotline for community members to report hate crimes. Not only did community members call the hotline for its intended purpose, but they also shared stories of how law enforcement officers smashed in the front doors and kidnapped the men in the house; or children reporting their father left for work 3 days ago but never came home; how they were being followed around town by men they didn’t know; or how Muslim-appearing men in the neighborhood were shoved into black vans and taken away. Similar to the violence against Black and indigenous people in the United States, the American government, through the police and immigration authorities, worked effectively to wage war on South Asian, Arab, and Muslim communities in the post-9/11 period through surveillance, family separations, and detention and deportations.

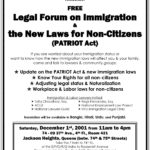

The Stop The Disappearances Campaign was a response to these situations—a way to offer resources for community self-defense, while building a working class movement to challenge the institutionalized racial violence in Black and brown communities in the United States. To prepare community members for increased contact with police and immigration authorities, DRUM offered legal clinics, Know Your Rights workshops, and other resources at mosques, community centers, and schools in South Asian, Arab, and Muslim communities. At the same time, community members came together to protest in solidarity with INS (and later ICE) detainees on hunger strikes in New Jersey and New York; they contributed to the anti-war struggle, recognizing the war on communities in NYC is intricately tied to the wars the US perpetrates in their homelands; and organized with Latinx and Black communities for safer and better work conditions. The campaign ultimately deepened the commitment to working class organizing in the South Asian community, particularly by cultivating the leadership of working class immigrant women and youth.

A critical element of DRUM’s work after 9/11 was organizing families impacted by the government’s targeting of Arab and South Asian men. The networks of connections, interdependence, and support cultivated by immigrants after migration were torn apart amidst the paranoia and confusion caused by racist state violence and surveillance. Many women found themselves in unimaginable situations — they had no way of knowing what had happened to their husbands and sons who were kidnapped and detained, and many were left without any financial support to sustain themselves or their children. It was under these conditions that women and young people led the fight to demand the release of their loved ones.

It was women and young people like Uzma Naheed, Zaida Parveen, Moni Alam, Shahina, and others who attended family gatherings hosted by DRUM where they would learn and share the details of what happened to their husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers. At these gatherings, families also learned that they weren’t alone. They saw the ways that the government’s anti terrorism policies were tearing through the fabric of the community and they were determined to fight back.

Throughout this timeline you will see women speaking out at rallies and protests about what happened to their husbands and brothers. You will also see the ways that young people strengthened their communities against racist attacks and confronted widespread fear. What will be harder to see—but you are encouraged to keep in mind—are all the ways that women sustained this work. Not only did they fight deportations and family separations, but women also took the lead in building networks of resistance and care, supporting their own and other families devastated by NYPD, FBI, and INS. It was by no means an easy task which these women faced—the pressures of organizing with the harsh reality of sexism and capitalism bearing down upon them. However, they did not give in to the repression and fear that rippled through the fabric of their communities. The efforts of these women and young people laid the groundwork for DRUM’s police accountability and gender justice work in the present. They imagined and modeled new ways of relating with one another that built community while mobilizing others to march for justice for not just their husbands and sons, but all who are impacted by the forces of state violence.

Our communities have seen immense growth of advocacy and service organizations. Ideas that were difficult to address 20 years ago, and especially in the years after 9/11 (like U.S. exceptionalism, imperialism, militarism and patriotism, community and law enforcement collaboration), are now much more openly challenged. And approaches towards abolition, ending capitalism, or the need for racial justice through deep and transformative solidarity with other communities, are much more widespread.

But the number of organizations doing mass-based organizing in our working-class communities has grown only a little, and not in proportion to the size or demands of surviving in a collapsing society. We need the full range of approaches (advocacy, education, services, legal, communication, and more) to meet all of our current needs and fight to create some breathing room from our current realities. But getting to the root of the crises and winning transformative change can only be achieved if we have fighting forces that only come through mass-based organizing.

The challenges we face are immense. The massive devastation in the Global South caused by the U.S. through ongoing wars, environmental destruction and the climate emergency, foreign interventions, and expropriative economic policies, keep creating an increasing number of migrants within and beyond our homelands. There's rampant militarization and criminalization of our people at borders, in the seas, and within borders on streets, our homes, our schools, our workplaces, and our faith institutions.

The challenges are also not only external to us. Internally, we also face immense challenges. Sectarianism. Professionalism and careerism within nonprofits. Individualism. Alternating between the two extremes of short-sighted pragmatism or ungrounded idealism. All driven by intersecting oppressions and cultivated by capitalism. Replaying the violence, harm, and abuse we have suffered onto each other within our communities and our movements.

The only place we can resolve these internal challenges, and confront the external challenges, at the scale that we need, is within and across our mass-based organizing and movement building. Only such organized forces can go beyond reforms or trying to reconcile ourselves with unjust systems, and instead lead efforts for genuine transformative change. It is within organized mass bases that we build and expand our capacities for how we treat each other, care for one another, test new forms of being and relationships, and model the different world we are trying to build.

The choices we make today, especially in how we want to take action, will determine what will be possible for us to do tomorrow.

*View timeline on desktop for best experience.

Timeline of DRUM Organizing 2000-2004

-

January to March 2000

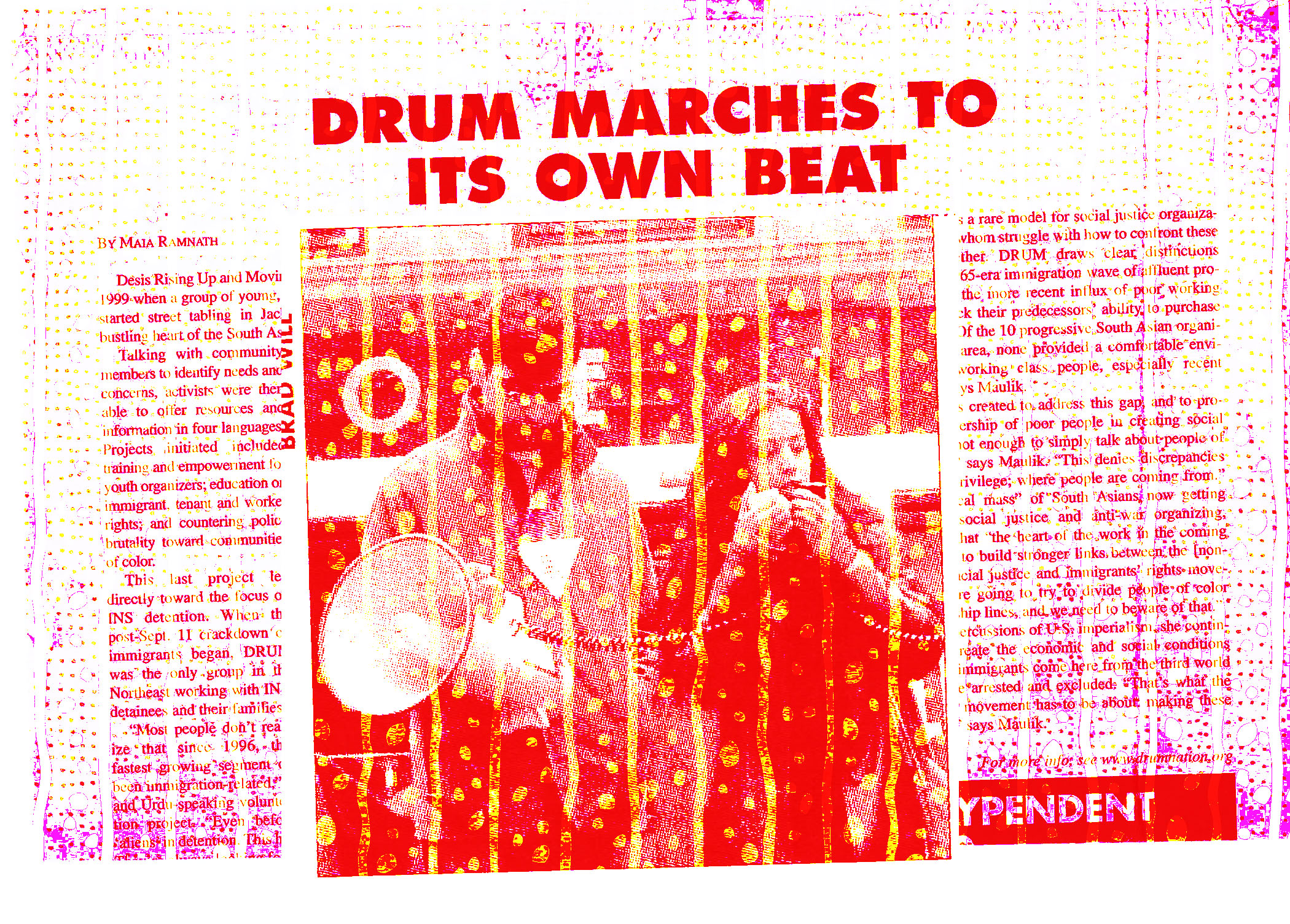

“Who can you speak to? Here comes the DRUM”

DRUM was founded by Monami Maulik, Asif Ullah, Shahed Chowdhury, Kazembe Balagun, and others. Newly formed, DRUM starts off the new year by holding meetings with dozens of youth, workers, street vendors, and tenants in Queens, identifying racial targeting of South Asian immigrants by the NYPD and INS as a critical issue in the community.

DRUM's Early Organizing -

April 2000

Police Murder of Amadou Diallo and 41 Days of Action

DRUM organizes a rally and march in Jackson Heights responding to the not guilty verdict in the police shooting of Guinean immigrant, Amadou Diallo, and also forms a coalition of over 20 Asian groups to launch a police and INS accountability campaign.

-

Summer/Fall 2000

Coalition on Detention and Immigration

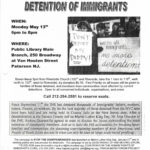

DRUM becomes active in the Coalition on Detention and Immigration, which launches a campaign in November to end detention abuses and demand access to Varick Street Detention Center. DRUM begins monthly gatherings for detainee families at Varick Street.

-

January 2001

INS De-Detention Project

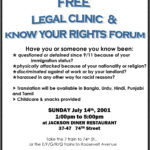

Subhash Kateel and Fahd Ahmed begin DRUM’s INS Visitation Project to Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey to connect and build membership among detainees. As part of this project, DRUM held public forums on detention through CODI to consolidate allies, and held multi-lingual community clinics with ally organizations for undocumented and non-citizen immigrants on 245i (LIFE Act) and other immigration laws.

Listen to this audio in which Fahd Ahmed, Executive Director of DRUM, talks about some of DRUM’s early work with detainees at the detention center in Elizabeth, NJ.

-

September 2001

The First Month after 9/11

Following the events of September 11, DRUM intensifies its anti detention work. DRUM becomes one of the first organizations of detainees and families to initiate grassroots organizing against the mass detentions of Muslim immigrants and the Patriot Act. In the months after 9/11, DRUM built relationships with 300+ detainees in detention centers in NY and NJ.

September 11, 2001 -

September 13, 2001

Reports of Disappearances

DRUM sets up a hotline for South Asian and Muslim community members to report hate crimes. Instead, they hear stories of family members, neighbors, and friends being disappeared by FBI, NYPD, INS.

In this interview from 2002, Monami Maulik, former Executive Director of DRUM, recounts the kinds of calls that the hotline would receive. From these calls, DRUM was able to locate and contact hundreds of South Asians and Arabs secretly detained directly after 9/11. This was a multi-lingual detention collect call hotline in Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, French, Spanish, Telegu, and Punjabi.

-

Fall 2001

Community Self Defense

DRUM launches the Community Self-Defense Campaign to equip immigrant communities, particularly South Asians, Arabs, and Muslims, with tools to defend against racial profiling and mass arrests.

In this audio clip, Monami Maulik details how DRUM members have been leading Know Your Rights workshops, developing rights curriculum and materials, and conducting training for hundreds of immigrants in mosques, schools, and community centers to build security, to provide advocacy and services, and initiate longer term anti detention and anti war organizing. DRUM works in partnership with NLG, Asian American Legal Defense & Education Fund, and Domestic Workers United.

-

January 2002

A Growing Number of Detainees

Leading up to the Stop the Disappearances Campaign, Monami Maulik highlights in this interview how since before September 11, immigrants were on track to become the fastest growing portion of the prison population in the U.S. DRUM’s ongoing work with detainees ramps up due to increased state violence against Muslim immigrants and their families after 9/11.

-

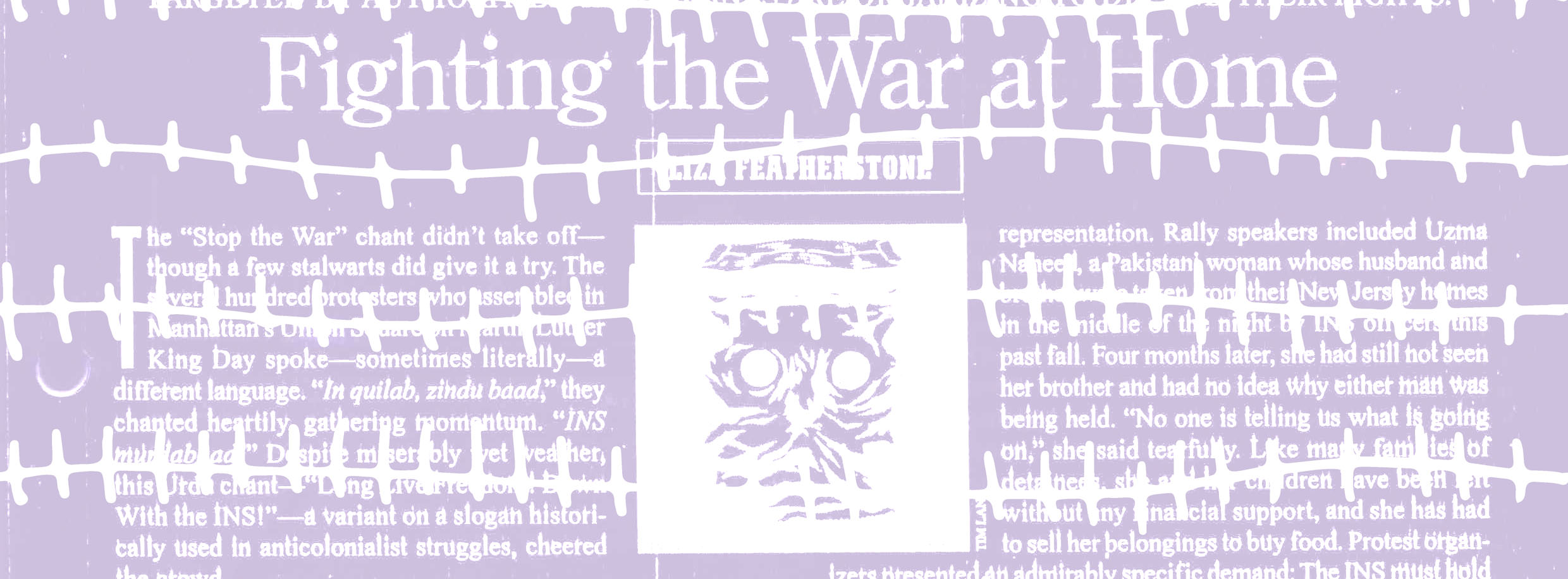

January 21, 2002 (MLK Day)

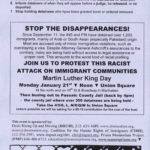

Launch of Stop the Disappearances Campaign

DRUM launches the Stop the Disappearances Campaign (STDC) with a press conference at Union Square Park attended by three hundred people, followed by bus caravans to New Jersey where 150 people rallied outside of Passaic County Jail and dozens rallied outside of Hudson County Jail.

The woman speaking in the header photo is Uzma Naheed, the first person to speak out publically about the post 9/11 sweeps. This was the first public action highlighting the disappearances of Muslims in the NYC area and poor conditions at INS jails. The campaign’s seven demands (including the release of all those held under immigration violations after 9/11, and the ‘independent monitoring of conditions in INS facilities) came directly from DRUM’s base of over 200 detainees at Passaic County jail and Metropolitan Detention Center.

Photos from the rally.

Stop the Disappearances Campaign -

Winter 2002

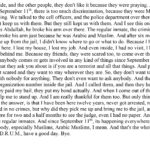

Detainee Testimonies

DRUM visits detainees weekly as a part of the INS De Detention campaign. In the following quotes and audio clips, a few detainees recount some of the conditions inside the jails.

From Q. Ali (name changed to protect identity)

Detained at Passaic County Jail.“America makes it so that we can only survive by leaving our countries and families to come here and then treats us like we are not human beings. “

From M. Zahir (name changed to protect identity)

Detained at Passaic County Jail.“When one of us spoke out to protest, they let the dog loose on that person too. One week later, the man who was severely beaten was gone- deported. I am willing to be a witness to this and so are others. If this country allows this kind of injustice, how can it talk about human rights?”

-

Spring 2002

INS Murdabaad!

Thanks to the organizing efforts of DRUM, Coalition for the Human Rights of Immigrants (CHIRI), and Prison Moratorium Project, among others, the INS allowed representatives from the ACLU and the American Friends Service committee to visit detainees in Passaic and Hudson County jails.

The coalition held another press conference with the ACLU and Human Rights Watch at the Federal building in NJ housing District Director Quarantillo’s office to demand that she hold her promise and meet with the public & families of detainees. Organizations also continued to pressure Edward McElroy, Quarantillo’s counterpart in NY.

-

May 2002

Public Forum at Passaic County Jail

Public Forum in Passaic County with INS and Sheriff to which the INS Director Quarantillo did not attend as promised, but Sheriff of Passaic County (holding largest number of post 9/11 detainees nationally at about 350 at the time) did attend. Testimonies given for public and media by former detainees of Passaic County jail, families of detainees at Passaic, and HELP (local Arab organization working through Patterson Mosque).

The forum prompted investigations into conditions at NJ county jails holding INS detainees by local and national media and DRUM was able to bring immediate medical attention to two detainees being denied health services for critical illnesses and win the release on bond of two others.

-

June/July 2002

Rallies at Metropolitan Detention Center and Middlesex County Jail

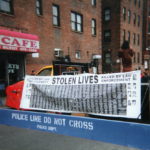

In June, the Stop the Disappearances Campaign organizes a march from Sunset Park, Brooklyn which ends in a rally at MDC (Metropolitan Detention Center). The rally brings together around 200 protestors and draws connections between immigrant anti detention and criminal justice. The families who rallied won the right to visit their loved ones at the facility.

In July, DRUM rallies at Middlesex County jail in NJ to investigate allegations of abuse (lack of medical care, unhygienic conditions, etc.). The rally succeeded in allowing the ACLU to tour and monitor the facility.

-

December 2002

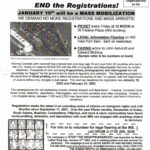

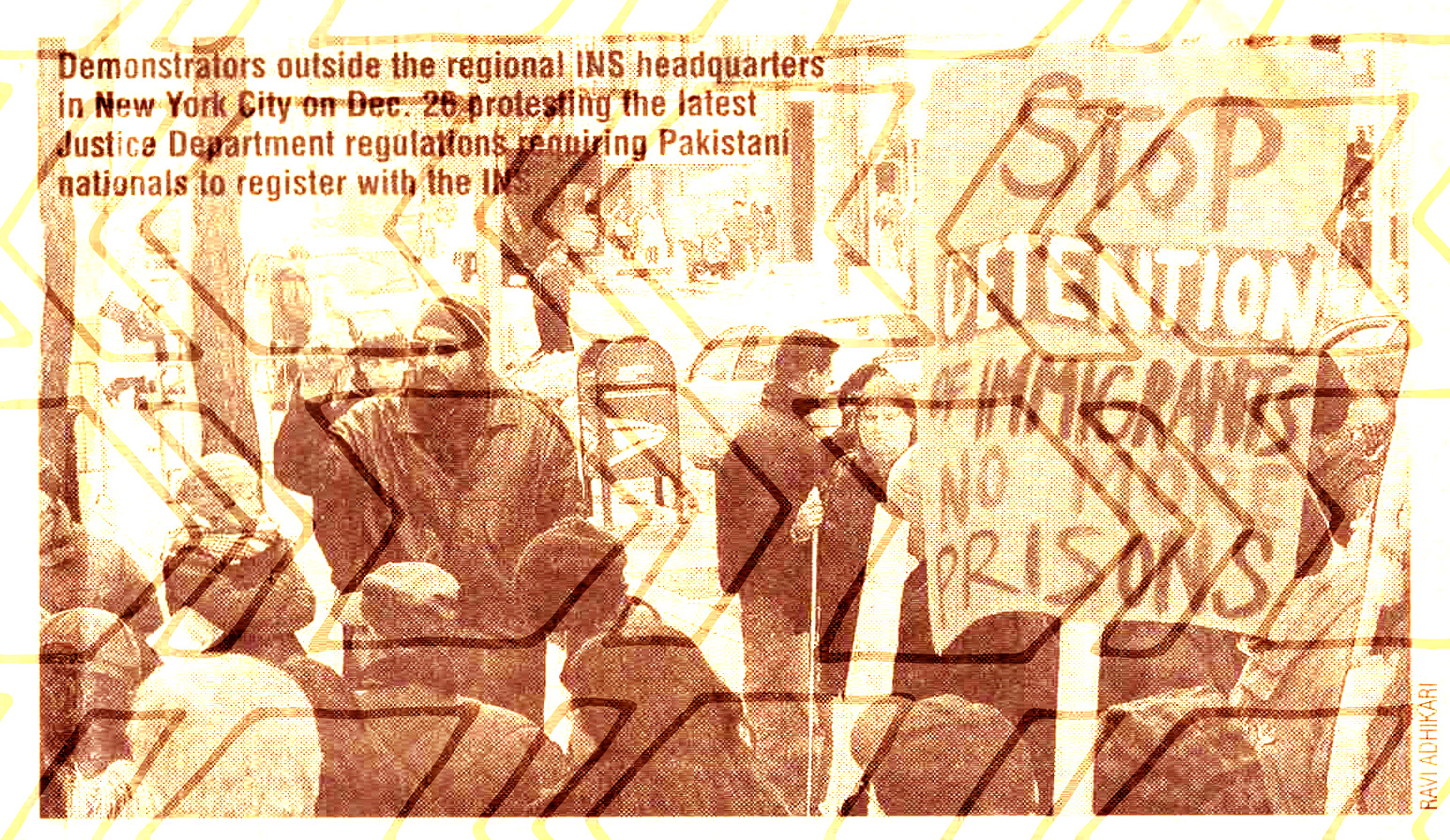

Mass Mobilization against the Special Registration Program

In December, the campaign launched a mobilization against the DoJ’s Special Registration program wherein boys and men from 20 primarily Muslim countries must register (fingerprinted, interrogated, photographed) by the INS. DRUM holds weekly pickets at 26 Federal Plaza culmination into a mass mobilization being jointly organized by over forty organizations on January 10th which is the registration deadline for people from 13 countries and on the next deadline on February 21st.

DRUM’s demands for both actions were developed directly with detainees arrested through Special Registrations. DRUM is recognized as the leading organization which has initiated this campaign. Over fifty legal, immigrant rights, civil rights, and community organizations responded to our open call for joint actions and attended the first planning meeting we organized on New Years eve.

-

January 14, 2003

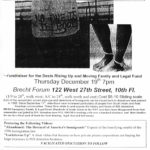

Farouk Abdel-Mufti & 5 others go on Hunger Strike at Passaic County Jail

Farouk Abdel-Mufti, a Palestinian activist detained in Passaic County Jail, goes on hunger strike with five other INS detainees to protest the indefinite detention of Arab and South Asians by federal authorities. Like many other post-9/11 detainees, Abdel-Mufti was detained on minor immigration violations and subjected to violence and abuse at Passaic County Jail.

Hear a statement from Farouk Abdel-Mufti five days before his hunger strike started, in which he calls for people to protest in the streets and organize for the freedom of all detainees.

-

March 2003

Stop the Disappearances Campaign Highlights

In March of 2003, DRUM presents at the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva, Switzerland by the Human Rights Law Group on the detentions and effects of the domestic War on Terrorism on the civil rights of South Asian immigrants in the U.S.

As a direct result of the campaign, DRUM has also released 60+ detainees through strategies of monthly action alerts, campaign mobilizations, letter writing drives and advocacy.

-

March 2003

8 Day Hunger strike at Passaic County Jail

Protesting horrid conditions and officer abuse at Passaic County Jail, eight detainees go on an 8-day hunger strike demanding to be transferred. Detainees detailed physical and verbal abuse by correctional officers, as well as the abusive use of attack dogs inside the facility. The trend of abuse and violence at Passaic County Jail was brought to the attention of human rights organizations.

“Since I’ve been in this jail, there’s been a lot of physical altercation. There’s a lot of racist name calling, and the officers disrespecting the INS detainees, treating us like dogs, like we have no rights at all. And there’s nothing we can do. Every time we write them up, try to rectify the problem, it escalates”

-Detainee Hunger Striker -

May 2003

operation homeland resistance actions

[/video]

Check out this video from Democracy Now! in which Monami Maulik explains the goals of Operation Homeland Resistance and connects it to the hunger strikes carried out by detainees in the past months.

DRUM in coalition with other immigrant rights and racial justice organizations coordinate Operation Homeland Resistance, a series of actions that would counter the U.S. government’s narrative that the war in Iraq was ending when in fact the occupation was only just getting started. Demands also include repealing racist “anti-terrorist” legislation and stopping the targeting of youth of color by military recruiters.

Three days of civil disobedience take place as a part of the campaign where over 100 people sign up to risk arrest. On the first day 41 protestors are arrested after blocking the entrance to 26 Federal Plaza, the building which houses the Bureau of Immigration & Customs Enforcement (now ICE, formerly INS).

-

Summer 2003

Day laborers arrested on Roosevelt Ave

Latin American Workers Project (PTLA) builds solidarity among day laborers who gather to look for work along Roosevelt Avenue. During this period, PTLA works to open a workers’ center in Jackson Heights in response to police arresting laborers and collaborating with immigration authorities. DRUM shares its hotline with PTLA and adds Spanish-speaking volunteers to manage calls from arrested jornaleros. DRUM, PTLA, Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund meet to develop a strategy to respond to the arrests.

“What’s been going on in terms of the harassment of day laborers has been happening in our community as well. If we bring together these two communities here we will be able to influence local officials more than if we just do this separately.”

-Monami Maulik -

October 2003

Hunger strike at Wackenhut Correctional Facility

DRUM supports ICE detainees on hunger strike at Wackenhut Correctional Facility in South Queens as they protest officer abuse and indefinite detention. Detainees demand timely processing of cases, the ability to be released on parole, end of abuse, and better medical treatment.

In this audio testimony, Rafik Sanusi, a detainee at Wackenhut describes how over 50 people are on hunger strike at the facility, details their demands, and calls for public protest.

-

October 2003

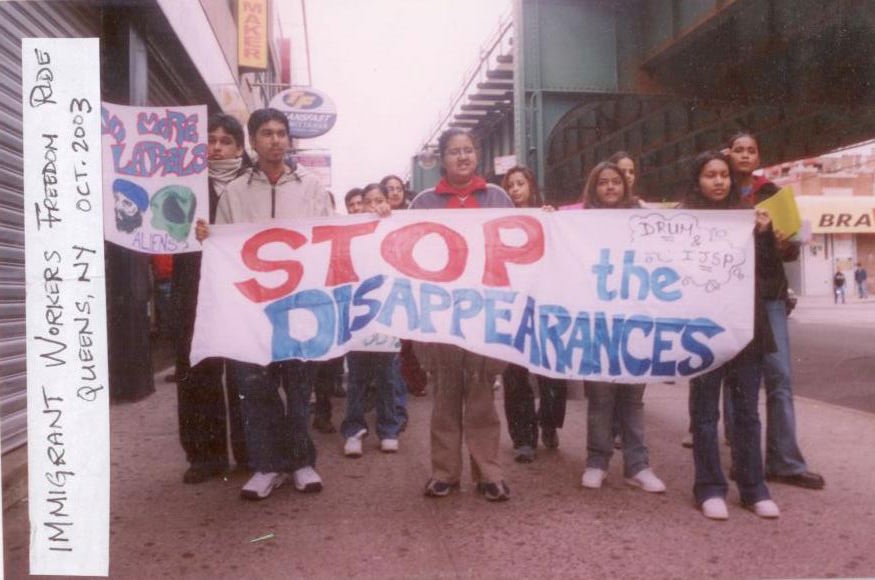

Immigrant workers freedom ride

Inspired by the historic Freedom Rides of the 1960s, labor and immigrant rights organizations organize the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride in order to bring attention to the issues facing different immigrant communities. Several buses left major U.S. cities to meet up in Flushing Meadows Park, Queens. The organizers of the ride aimed to put immigrant workers’ rights and indefinite detentions after 9/11 on the agenda ahead of the 2004 presidential elections.

-

Fall 2004

Anti War Protests at the RNC

]

In the fall of 2004, the Republican National Convention was set to occur in New York at Madison Square Garden where the Republicans would nominate Bush and Cheney for their second term. Thousands marched to protest the Bush regime and the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the video above, titled Raising Up the Alams, the Alam family shares how post 9/11 policies impacted their lives. Mohammed Alam shares his experience with special registration and how immigration officers threatened him. Later in the video, Moni, his wife, encourages him to go to the RNC protests. Moni gives a powerful speech at the protest demanding justice for all immigrants and that Bush and Ashcroft “GO HOME!” In the video, both Moni and Mohammed draw connections between the war against immigrant communities in the U.S. and the wars abroad.

Various anti war protests from this period.

Timeline of DRUM Organizing 2005-2009

DRUM’s work in the post 9/11 period around detentions, sweeps, and special registrations yielded nearly 900 members. By early 2004, more than 90% of those members were either deported or self-deported. This prompted some deep questions about our organizing model: What is the point of organizing if we can’t build a base?

While it was critically important for us to respond to the post 9/11 sweeps, the Special Registrations, and other similar programs, our assessment was that we can’t build and sustain a base on such crisis response work. So in 2004-2005, we shifted to organizing on more bread and butter issues: education, policing in schools, immigration reform, immigrant access to driver's licenses, etc. These shifts allowed us to build a sustainable base, which combined with intentional political education and relationship building then allowed us to more robustly respond to emerging crises with a larger and prepared base of people.

After the utter failure of the post 9/11 sweeps, which rounded up more than 1,200 men yet found zero connections to terrorism, there was a growing critique of the government’s and law enforcement’s policies and tactics. This was also spurred by the public actions that DRUM was organizing with impacted families and outside Passaic County jail. By March and April of 2002, law enforcement switched to a ‘community relations’ approach of ‘working with the community.’ Based on our learnings from Black and Puerto Rican movement elders, we knew that this was a ruse to infiltrate and surveil our communities. But much of our communities were living in fear, and wanted attacks from law enforcement to stop and gave in to these efforts.

Immediately we started to see people being asked intrusive questions and being asked to become informants, or be recruited to join law enforcement as officers. This was the moment that the surveillance of our communities rapidly expanded by both the FBI and the NYPD. Also soon after we started to see ‘terror plots’ that had heavy involvement of paid informants and undercovers, who essentially instigated and manufactured the plots by targeting vulnerable people within our communities.

These same cases were then used to propagate theories of ‘homegrown threat’ and ‘radicalization’, all of which led to further funding for and expansion of surveillance within our communities, and also beyond our communities. The same surveillance apparatus was used to spy on activists against police brutality, anti-war protestors, environmental and animal rights activists, etc.

DRUM supported and organized with many of these families, whose loved ones were targeted and entrapped, in the NYC area. The Siraj family being the most notable example. But it wasn't until the Fall of 2011 when the Associated Press leaked documents about the NYPD spying program that we had public confirmation of what we had been experiencing and saying for many years already. With that confirmation, we were able to much more openly organize against surveillance.

-

April 2005

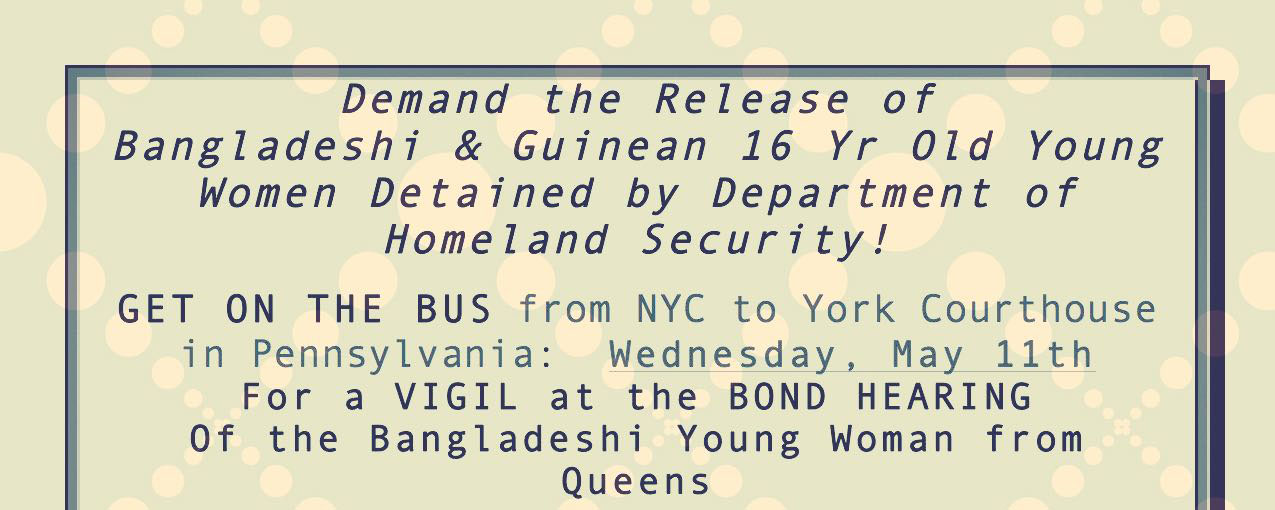

First Federal Terrorism investigation involving minors— Tashnuba Hayder & Adama Bah

In April of 2005, two 16 year old Muslim girls, one from Bangladesh, Tashnuba Hayder, and the other from Guinea, Adama Bah, were detained incommunicado. For six weeks they were kidnaped by the state based on flimsy reports, later proven false, that the girls were potential recruits for a suicide bomb plot. Tashnuba was eventually deported with her family, and Adama survived her deportation proceedings but left with devastating consequences.

DRUM joined the Ad Hoc Coalition and led actions for them to be brought before court, get bonds, and be released.

Articles:

Questions, Bitterness, and Exile for Queens Girl in Terror Case

Remember the Two 16-Year Old Girls Arrested As Suicide Bombers?

-

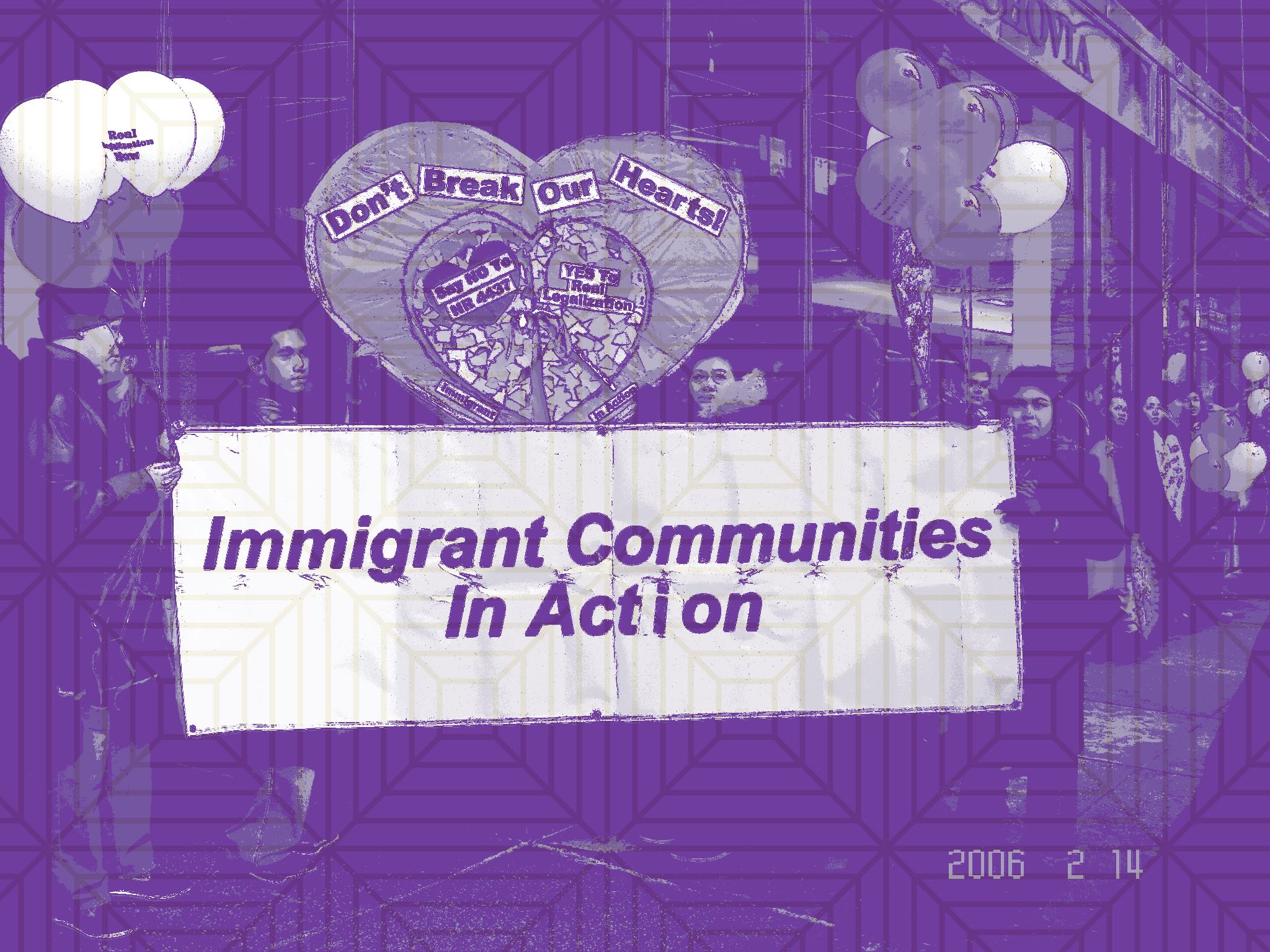

Spring 2006

Immigrant Communities in Action

DRUM in coalition with Latinx, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and Desi immigrant organizations forms the Queens Drivers’ License Coalition (QDLC) to protect the right of immigrants to drivers’ licenses in New York State. As attacks on immigrants intensify across the U.S. the QDLC, active since 2005, becomes Immigrant Communities in Action (ICA).

The militarization and increased surveillance at the US-Mexico border are directly connected to the state violence immediately following 9/11. Bush appoints Chertoff–who played a major part in post 9/11 detentions and disappearances–as the head of the Department of Homeland Security.

Confronting the proposed increase in immigration enforcement and the repression of immigrant activism, ICA holds monthly actions, press events, and advocacy meetings with congress. ICA also holds multilingual coalition meetings of over 100 to 150 community leaders speaking at least six languages and planning the coalition’s next moves.

-

May 2006

Mega Immigration Marches

With HR 4437, also known as the Sensenbrenner Bill, passing in December 2005 in the House of Representatives, the wave of anti-immigrant sentiment increases. The bill criminalized undocumented immigrants and their allies in a way that shifted enforcement to include state and local authorities.

In protest of the Sensenbrenner Bill, the proposed Guest Worker Policy, and Bush’s intention to station 6,000 national guard troops at the US border with Mexico, immigrants all over the US rise up and take part in historic mega immigration marches. Millions march in the spring of 2006, demanding protections for immigrant communities, comprehensive immigration reform, and a pathway to citizenship.

Immigrant Communities in Action plays a significant role in NYC by mobilizing hundreds of directly impacted communities and thousands in April and on May Day. On May Day, immigrants take part in “the Day without an Immigrant” staying home from work or school in order to demonstrate the massive labor power of undocumented workers.

-

June 2006

National Emergency Delegation to the U.S. – Mexico Border

DRUM delegates participate in the “National Emergency Delegation to the U.S. – Mexico Border” with the National Network for Immigrants and Refugee Rights. The delegation is organized in response to deaths at the border reaching record highs. People come together to bear witness to the violence committed at the border on Indigenous lands claimed by both the US and Mexico. In large part, these deaths are the result of policies of militarization at the border influenced by the post 9/11 environment of tightening national security and general anti-immigrant sentiment across the US.

As a result of the trip, delegates gain an understanding of how post 9/11 US military and imperial policies cause more people to flee their homelands and cross the border. At the same time, increased militarization and national discourse around the border have an impact on legalization and general sentiment towards immigrants throughout the US.

Understanding the interconnectedness of the border with the rest of the country, DRUM membership develops an ethos of evaluating immigration proposals and reforms based on how it would impact communities at the border. DRUM members commit to not throwing communities at the border under the bus by supporting reform that would increase enforcement and further criminalize crossing the border.

-

Summer 2006

Education not Deportation

After 9/11, South Asian, Arab, and Muslim students face discrimination and harassment in schools. Youth Power! conducts a two-year survey to study the impact of NYC’s school safety policies on over 650 South Asian students in middle and high schools.

The “War on Terror” in public schools gives rise to more collaboration between local law enforcement, homeland security, and immigration authorities which creates an environment of fear and insecurity among immigrant youth and their families. During this period, DRUM members encourage youth to submit opt-out forms their information wouldn’t be shared with military recruiters preying on students.

-

July 2006

Israeli Wars in Lebanon and Gaza

Other countries adopt the logic of the “War (of) Terror.” While Israeli colonialism and zionism have a long history, we observe that the Israeli government uses the framings of the “War (of) Terror” to justify attacks in Gaza and Lebanon. The wars on Gaza and Lebanon are used as a way to intensify surveillance here in the US on our communities—the state surveils those who sympathize with people resisting in Gaza and Lebanon.

DRUM members join mass mobilizations in New York and Washington DC to call for Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon and Gaza. In the interview above, listen to DRUM youth share why they came to the rally. They speak out against the Israeli occupation and its connections to US imperialism and military aid. One young person also draws connections between the displacement of the Palestinian people from their lands and the dispossession of immigrants which drives their migration to the US.

-

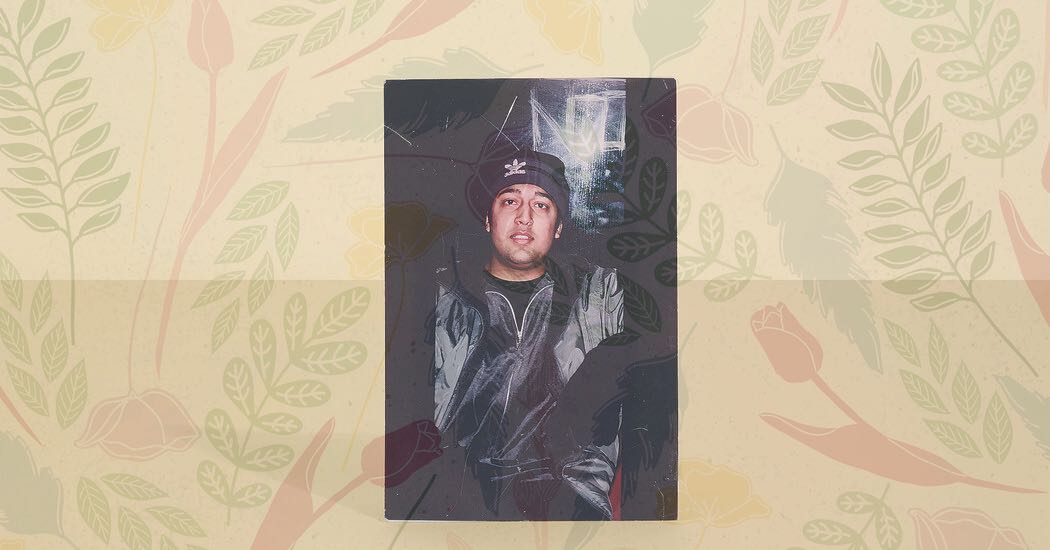

January 2007

Matin Siraj Sentenced to 30 Years in Prison after NYPD Entrapment

In 2004, Shawahar Matin Siraj was arrested by the NYPD after a police informant entrapped him in a manufactured terrorism case. In 2007, he was sentenced to 30 years in prison. The day after his sentencing, Matin’s family was arrested by ICE officials and placed in detention for days. DRUM mobilized for the family’s release, and since then, Matin’s mother, Shahina Parveen, has been at the forefront of speaking out against the post 9/11 law enforcement surveillance policies.

The ‘Herald Square Bomber‘ Who Wasn’t –Article about NYPD Entrapment of Matin in the New York Times

Shahina has continued to build relationships with Black and Latinx families who have lost their loved ones to NYPD killings, as well as with immigrant families who have lost loved ones crossing the militarized US-Mexico border, and with communities across the world impacted by militarism. Her work laid the foundations for the historic partnerships in the police accountability movements between those working on street policing and those working on surveillance.

Surviving Surveillance, Catering to America: Shahina Parveen— Short Documentary piece about the impact of Matin’s incarceration on his family.

Democracy Now Interview with Matin’s Lawyer Martin Stolar

-

October 2009

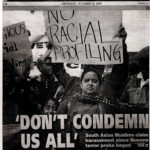

FBI Surveillance in Flushing, Queens

The FBI and NYPD conduct raids and surveillance targeting the Afghan community and Muslims in Flushing in response to a suspected plot to bomb parts of the subway system. DRUM organizers connect with more than 100 women who live in the buildings which were raided. These women share that their husbands were stopped by the police while on their way to work, made to show ID and answer all sorts of questions about where they’re going and what they know about the suspected plot.

DRUM organizes an anti- FBI raids protest outside Flushing library and conducts Know Your Rights trainings across Queens.

The End Racial Profiling Campaign launches. DRUM partners with CUNY Law to create a database of complaints on racial profiling by the FBI and submits a series of recommendations that protect civil liberties. The campaign wins the end of the raids and some changes to FBI practices.